The auditory aptitude tests—Tonal Memory, Pitch Discrimination, and Rhythm Memory—are longstanding components of the Johnson O’Connor Research Foundation test battery. They were first administered in the 1940s as part of the larger group of Seashore music tests that included time, loudness, and timbre discrimination. These were pared down to the current three tests in the late 1970s. They have been adapted to new technology but remain essentially the same. The unchanging significance of these tests is evidence to the timelessness of the auditory aptitudes themselves. This year Linda Houser-Marko did a study of a few different aspects of the auditory aptitude tests.

The three auditory aptitudes together

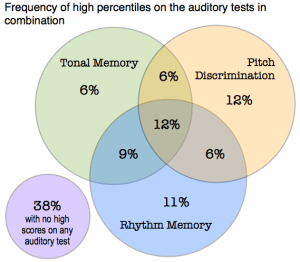

In order to look at the auditory aptitudes as a set, we examined scores that were 70th percentile or higher in our dataset of 64,670 examinees. Groupings of examinees were made according to their auditory scores: high in all three, high in two, high in one, or high in none. The composition of the general population of examinees is shown in the figure on the next page.

About 12% of our testing population scored high in all three of the auditory aptitudes. About 21% of the examinee population scored high in two auditory aptitudes, about 29% scored high in one, and about 38% of the population scored high in none of the auditory aptitudes.

Auditory aptitudes and music

The three auditory tests take a singular approach to different aspects of auditory talents such as memory and intonation, and can be thought of as a set of music aptitudes. We confirmed this auditory aptitude and music connection by looking at aptitudes, college majors, and occupations. Examinees who majored in music in college had higher than average percentiles for the auditory tests: Tonal Memory mean was at the 89th percentile, Pitch Discrimination mean was at the 84th percentile, and Rhythm Memory mean was at the 80th percentile.

Musicians specifically

There were 144 examinees in the dataset who indicated that their occupation was “musician” (occupational code 152, without any limitation of job years). On average, their percentiles for the auditory tests were similar to the music majors. Of the 144 musicians, 54% had been music majors.

Auditory aptitudes and other aptitudes

The association between music and math has had a long history of theoretical support partly because of the similar basic principles and relationships within both areas. Music training has been shown to be associated with an increase in spatial and math skills in young children in an experimental intervention (Rauscher & Hinton, 2011). However some research has found that the relationship is not absolute—one study found that mathematicians were not more likely to be musical (Haimson, Swain, & Winner, 2011), though that study did not involve auditory ability tests. We wanted to know more about the relationship between auditory abilities and numerical abilities. We found that the auditory aptitude scores were correlated with scores for the tests of Number Series, Paper Folding, Wiggly Block, Memory for Design, and English Vocabulary.

The auditory aptitudes have also been thought to be associated with the pronunciation and intonation aspects of foreign languages. In an earlier questionnaire study conducted by the Foundation, foreign language learning and auditory abilities were associated. People who stated that foreign languages were “easy to learn” had higher auditory scores (SB 2011-19) compared to others who did not feel that way about foreign languages. We explored this further by looking at college majors, and found that examinees who had majored in a foreign language had higher than average auditory aptitudes, as can be seen below.

College majors and occupations

Next, the levels of the auditory scores were examined for individuals grouped by their college major that was stated on the information sheet. There were about 38,000 examinees in this dataset who were either in college or had been in college, and for whom we had college major information.

Quite a few college majors stood out as groups in which the mean level of one of the auditory scores was higher than average (i.e., z > .20, which is about the 58th percentile). Foreign languages, humanities, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, physical science, and theater were all college majors in which people had notably high auditory scores. For occupations, the auditory aptitudes were generally higher for examinees in careers such as architects, medical doctors, professors, theater artists, and writers, as well as musicians.